Simon Hantaï

Bio Exhibitions Works Publications Press

Simon Hantaï: Canonical at last?

by David Carrier, Two Coats of Paint, Feb 28, 2024

Simon Hantaï, Centre Pompidou

by Molly Warnock. Artforum, Sep 2013 issue

Simon Hantaï's Discontent

by Gwenaël Kerlidou. Hyperallergic, Sep 7, 2013

Simon Hantaï and the International Scene

by Paul Rodgers. Artpress #402, Jul-Aug 2013

Hantai in America

by Carter Ratcliff. Artpress, supp. to #401, Jun 2013

National Gallery of Art Acquires Major Work by Simon Hantaï

by the National Gallery of Art Press Office, Apr 6, 2012

Letter from New York

by Ben Lerner. Lana Turner Journal, Jun 28, 2010

Simon Hantaï, Painter of Silences, Dies at 85

by Margalit Fox. New York Times, Sep 30, 2008

Simon Hantaï (1922-2008)

by Raphael Ruinstein. Art in America, Dec 2008

Simon Hantaï: Canonical at last?

by David Carrier | Two Coats of Paint, February 28, 2024

What comes after Abstract Expressionism? A couple of generations ago, American art writers were intent on addressing that question. The American color field art of Morris Louis, Kenneth Nolan and Jules Olitski was one plausible answer. Then, of course, came Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and much more. The French had a different answer. They were interested in the abstraction of Hungarian-born Simon Hantaï (1922–2008), who moved to France in 1948 and whose work seemed in line with the post-structuralist theory that had taken hold there. His inspirations were Marxism, Catholic tradition, Matisse, Picasso, and Jackson Pollock as seen in Paris exhibitions, and his bête noire was Surrealism. Given these rich and disparate interests and impulses, it goes almost without saying that Hantaï developed a highly distinctive aesthetic. Long famous in France, his paintings recently have been shown in several ambitious Manhattan galleries, notably Timothy Taylor.

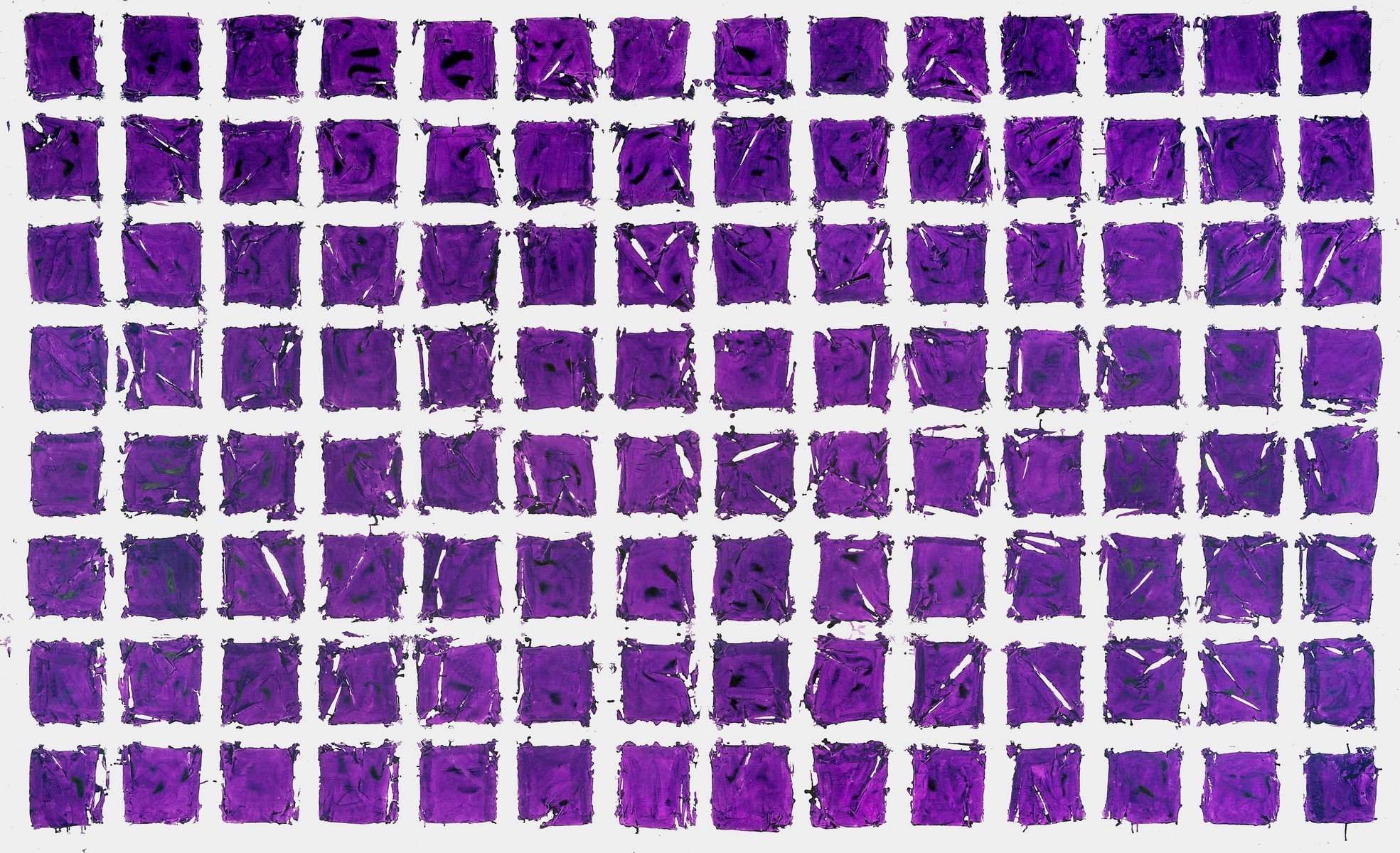

With eleven large canvases, “Unfolding” provides a cogent account of Hantaï’s development. In Meun (1968), painted in oil, we see floating organic body parts, abstracted versions of the forms in Matisse’s late cut-outs. Then Bourgeons (1972) presents smaller blue forms set in an all-over composition. The later works are acrylic. On Tabula (1980) and Tabula (1981), Hantaï sets rows of painted forms on a grid. Whereas Louis soaked his canvas, Hantaï knotted, folded, or crumpled it before unfolding and then stretching it. Using diverse techniques, both artists thus sought a radically impersonal way of using color. Both also chose to set their color in backgrounds of unpainted or underpainted canvas.

Understood in that way, Hantaï’s and Louis’s respective bodies of work are complementary. Molly Warnock, curator of the show, sees Hantaï’s oeuvre a bit differently. She connects it to the writings of Jacques Derrida and the deconstructionists, according it a complicated interpretation akin to the one Michael Fried extended to Louis’s. Whatever its merits, that critique should not occlude either the visual affinities between the two artists’ paintings or the independent merit of Hantaï’s. Both were abstract painters concerned with de-skilling, as it became known in America. There is no reason both Hantaï’s and Louis’s ways of making abstractions shouldn’t be embraced equally. And the delayed American appreciation of Hantaï – in part the product of a broader reaction against French modernism – should not now be held against him.

One complicating but undeniable factor is that Hantaï’s style of abstraction is an alternative to the work of Johns, Rauschenberg, Pop Art in general, and indeed everything since. But we art writers are familiar with the compulsion to edit art history, and we’re obliged to stay alert to under-appreciated art that belatedly calls for the canon to be revised. On this score, Hantaï’s work qualifies simply because it is obviously visually convincing. His paintings deserve to stand alongside the works of the American color field painters. How, then, can we rethink our analysis and acknowledge Hantaï’s legitimate importance? Answering that important question may be demanding. But we will need to alter our historical framework at least a little. And that is worth doing, I believe, because, wholly apart from any historicist theorizing, Hantaï has a unique and convincing place in the development of late modernism.

“Simon Hantaï: Unfolding,” Timothy Taylor, 74 Leonard Street, New York, NY. Through March 2, 2024.

About the author: David Carrier is a former professor at Carnegie Mellon University; Getty Scholar; and Clark Fellow. He has published catalogue essays for many museums and art criticism for Apollo, artcritical, Artforum, Artus, and Burlington Magazine. He has also been a guest editor for The Brooklyn Rail and is a regular contributor to Two Coats of Paint.

Simon Hantaï, Centre Pompidou

by Molly Warnock | ARTFORUM Sep 2013

SIMON HANTAÏ IS OFTEN PRESENTED as Europe’s answer to Jackson Pollock: The Hungarian-born French painter was among the first on the Continent to notice and take seriously Pollock’s painting, and the abstract canvases he produced over a period of twenty-two years, from 1960 to 1982—in the medium that he called pliage, or “folding”—are also seen as a precedent for the variously “deconstructive” or “analytic” tendencies associated with a host of younger figures, including Daniel Buren and the painters of Supports/Surfaces. Yet Hantaï’s pliage works, widely exhibited in France during the later 1960s and ’70s (and increasingly visible in New York of late), comprise only one, albeit sustained, period within a larger and decidedly heterogeneous oeuvre—much of which remains unknown and largely inaccessible. Many important paintings entered private collections early on, while the artist himself refused all but a handful of invitations to show his work in the final quarter century of his life. Five years after the painter’s death, and nearly forty years after his last retrospective, Hantaï’s art is ripe for reassessment.

The expansive full-career survey held this summer at the Centre Pompidou constituted an important step in that direction. Organized by poet-critic Dominique Fourcade, former Musée National d’Art Moderne curator Isabelle Monod-Fontaine, and outgoing Pompidou director Alfred Pacquement—three longtime admirers of Hantaï’s art—and arranged chronologically, the show brought together 130 paintings spanning almost the entirety of the artist’s career in France, from shortly after his arrival in Paris in the fall of 1948 through the later ’80s and ’90s, when he produced his final paintings. Previously obscure periods, such as Hantaï’s Surrealist phase between 1952 and 1955, were given unprecedented coverage, and long-separated paintings were reunited—some, as in the case of the pivotal Peinture (Écriture rose) and À Galla Placidia, both 1958–59, for the first time since they left the painter’s studio. The sheer depth and breadth of the work on view clearly established Hantaï’s place among the most searching and protean artists of the later twentieth century.

What was lacking, unfortunately, was a compelling reading of the logic of the work, its driving commitments and stakes—in other words, an explanation of how one room led to the next. This was partly a result of a clear decision, at once voiced and enacted by Fourcade in his long framing essay for the accompanying catalogue, to exclude from consideration all topics deemed to lie outside the domain of painting. One effect of that refusal was a marked avoidance of Hantaï’s own writings and remarks about his work (including the painter’s extraordinary and still underread texts of the ’50s, so intimately entangled with his pictorial practice), which were cast by Fourcade as an obfuscating screen. Another effect, closely related to the first, was a tendency to let judgments of quality and appeals to a transhistorical notion of “la grande peinture” stand in for a more rigorous exfoliation of the issues in play.

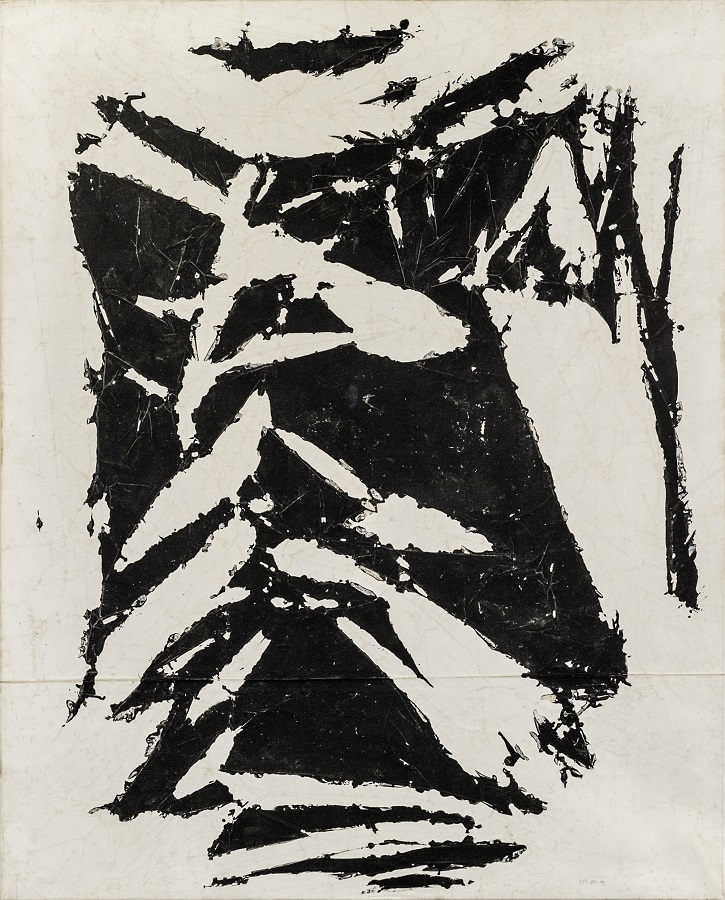

Those issues, as the work itself made clear, are large and complex—and touch upon matters as fundamental as what it means to be a finite self, exposed to contingency and loss. Perhaps the most consequential, and certainly one of the more striking, stories told by the more than fifty rarely seen (for the most part scraped) works tracking Hantaï’s first decade in France concerned his palpable ambivalence toward questions of embodiment and being. The disquieting, suggestively humanoid, and intensely sculptural monsters at the center of Femelle-Miroir I and especially Femelle-Miroir II, both 1953—figures green like the Christ in Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar, France, which Hantaï had visited shortly before—emerge against the backdrop of more experimental, allover compositions, and come off as self-inflicted obstacles, devised in order to work through and overcome the limits of physical representation. For what then transpires is a veritable passion of figuration: a stripping bare or sustained undoing that begins in earnest with Hantaï’s departure from the Surrealists, his move to gestural abstraction, and his momentary rapprochement with his fellow painter Georges Mathieu. The key stations here are Sexe-Prime. Hommage à Jean-Pierre Brisset, 1955, with its flayed-looking figural clumps and exposed underpainting, and Souvenir de l’avenir, 1958, in which painting is reduced to basic oppositional pairs: black and white, horizontal and vertical.

Those negotiations brought one in turn to the heart of the show: a large and visually stunning room devoted to Hantaï’s work from the roughly one-year period stretching from the late fall of 1958 through the final days of 1959. The linchpin of the installation, as of the artist’s career as a whole, was the canvas now called Peinture (Écriture rose), a vast expanse covered with passages copied by hand from biblical, liturgical, and philosophical texts, along with various other pictorial incidents such as areas of gold leaf and a spray of black ink. Hanging directly beside it, the slightly smaller À Galla Placidia revealed a surface layered with minuscule touches of paint strongly reminiscent of mosaic (a resonance reinforced by the title, given in honor of the fifth-century mausoleum at Ravenna). Developed adjacently in Hantaï’s studio, and intimately linked in his daily rhythm, these monumental paintings now belong to different museum collections: the former to the Musée National d’Art Moderne, the latter to the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. Their reunion at the Pompidou therefore constituted an event, the significance of which was only amplified by the additional inclusion of thirteen roughly contemporaneous paintings, from a larger gold monochrome to a host of smaller paintings also deploying writing, what the artist called petites touches (“little touches”), or both.

Within the terms of the exhibition, these paintings mark the advent of a new kind of pictorial space and therefore the moment when Hantaï, according to Fourcade, “invented his own originality.” Remarkably, however, the exhibition had nothing of substance to say about the works’ explicit appeals to devotional and liturgical supports and milieus. Yet at stake in these works is nothing less than a summing up and a sustained farewell to an entire past of painting in the West: that of its traditional embedment in a ritual and primarily Catholic context that, as Hantaï had come to understand it, once secured painting’s meaningful being for a community. Incomprehensible simply as new avatars of Pollockian “alloverness,” these paintings pose an open question about the place (or nonplace) left to painting under secular modernity—after or beyond a certain promise of communion. What one makes of this will largely determine what one makes of the pliage work on view in the following rooms.

Repeatedly modified from one series to the next, and first qualified by the artist as a “method” in 1967, pliage names the painting of a crumpled, knotted, or carefully folded canvas that is then unfolded and stretched for exhibition. Read along the trajectory I’ve proposed here, pliage helps Hantaï recover finitude and tactility as matters of the decidedly material support and its handling. In so doing, it takes over and transforms the promise of Peinture (Écriture rose): Whereas the earlier painting approaches Western thinking about “the sacred” as, among other things, a body of texts—bound to history and exposed to reading—pliage further emphasizes the material contingency, even the lowness or banality (a key word for Hantaï), of painting in the wake of that tradition. Which is to say: modern painting.

The complexity of that passage was largely elided in this show, which stayed within the broad lines of a reading sketched by Fourcade as early as 1976. Here Hantaï appears as a gifted colorist settling into his mature reckoning with Pollock, subsequently remaking Matisse and eventually Cézanne in light of that engagement. (Notably absent from this presentation, albeit addressed in the catalogue, was any sense of his dealings with Duchamp, a figure who must now be counted among Hantaï’s most enduring, if comparatively subterranean, interlocutors.) Two bodies of work in particular were clearly privileged and shown in depth: the inaugural “Mariales,” 1960–62, with fifteen paintings, and the equally decisive “Meuns,” 1967–68, with eighteen canvases. Whereas the former group reveals densely packed surfaces combining opaque painted facets and underlying areas of black drips or bare canvas, the latter series was the first to allow nonpainted reserves to penetrate fully the painted areas. The transition between the two reveals the painter struggling to acknowledge the potentially constitutive role of blank or white space, which he had initially perceived as merely disruptive. Additional rooms tracked his later peregrinations among the nonpainted, from the more dispersed, allover configurations of the “Études,” 1968–72, and the “Blancs,”1972–74, to the comparatively regular grids of the late, long-running “Tabulas,” 1972–82.

Here as elsewhere, however, the orientation toward “great painting” had its costs. Foremost among them was a relative monotony in the installation, with the curators opting consistently to display the most monumental works of a given period. Yet as Georges Didi-Huberman rightly notes in his contribution to the catalogue, Hantaï throughout his life purposefully alternated between larger and smaller supports—both within series and across them. This variety is key, for it speaks both to the experimental and empirical nature of pliage, and to the larger oscillation in Hantaï’s work between immersion and circumscription, between the desire to “lose himself” in painting and the active recovery of limits. That dynamic was all but evacuated in this show, nowhere more evidently than in the awkward corner room devoted to two early series, the “Catamurons,” 1963–64, and the “Panses,” 1964–65: Both are composed primarily of smaller formats, but were represented almost exclusively by larger examples.

Related omissions haunted the exhibition’s final room, devoted to Hantaï’s production in the long years following his withdrawal from exhibiting his work in 1982. His final series of paintings, titled “Laissées,” were produced between 1989 and 1998, and are composed in part of fragments cut from a group of extremely large-format “Tabulas” from 1981. The later series refigures the artist’s exploration of pictorial edges and boundaries as a quasi-photographic practice of cropping, and is in that sense continuous with several roughly contemporaneous experiments with anamorphic, photographically based silk screens and, shortly thereafter, with digital scanning and printing. Although barely acknowledged in the Pompidou exhibition, such investigations suggest Hantaï had once again taken up his enduring interest in painting’s adjacency to a range of practices that exceed it. What this photographic turn figures is neither a resurrection nor a rebirth, but a “remaining”: so many apparitions of a finite and contingent medium, endlessly displaced beyond itself.

Molly Warnock is an assistant professor in history of art at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

[Back to press]

Simon Hantaï’s Discontent

by Gwenaël Kerlidou on September 7, 2013

HYPERALLERGIC

“I said to my students: First and foremost, if you want to be painters, you’ll have to cut your tongue off, because this decision will take away from you the right to express yourself in any other way than with your paint brushes.”

—Henri Matisse, Écrits et propos sur l’art. Hermann, Paris.

In 1983, at the height of his career, Simon Hantaï (1922–2008), then sixty years old, decided to withdraw from the art scene and stop exhibiting his work, if not to stop painting altogether. He would not show again until 1998, a fifteen-year hiatus and self-imposed silence that echo with more force as time goes by. Why, we may wonder, would an artist at the top of his game, especially someone of Hantaï’s stature, do such a thing? The question has haunted me for years. With the current exhibition at the Musée national d’art moderne Centre Pompidou in Paris and two solo shows in Chelsea galleries this summer, the moment has come for a long overdue reexamination of his achievement and legacy, and of this hiatus in his career.

In the mid-seventies, Hantaï had risen to prominence on the Paris art scene with paintings produced through a very idiosyncratic process of “pliage,” which combined the automatism of Surrealism with Jackson Pollock’s all-overness and Henri Matisse’s color fields. Rapidly: It consisted of folding a piece of primed canvas according to different patterns in each series of work, covering the folded canvas with paint in one solid color, and presenting the unfolded and re-stretched result to the public.

What commands our interest is that, among the plethora of artists and painters who worked from the beginning of the seventies through the end of the eighties, and who for the most part embraced the new market-dominated art world, Hantaï’s gesture of resistance and retreat was so singular as to be lost in the brouhaha of the new marketing and money-making machine. The exceptional example of his stance and its symbolical consequences are only becoming clearer today, five years after his death.

The early eighties were a turning point in the art world and in the economic world at large. In 1981 in the US, Ronald Reagan was elected and immediately instituted an aggressive, business-friendly and ideologically conservative agenda. By contrast, that same year in France, where Hantaï lived, Francois Mitterand, a socialist, was elected. With Jack Lang at the helm of the ministry of culture, the new government had launched, against all expectations, an ambitious program of cultural initiatives that took everyone in the art world by surprise. In 1982, Hantaï had become a primary beneficiary of this new political program as the official French representative at that year’s Venice Biennale, and more official recognition was on the way.

But, on the contemporary art scene, 1983 was gearing up in a direction quite different from the one Hantaï’s work was taking. Neo-expressionism was on an unstoppable rise. Young (and sometimes not so young) Italian and German painters had burst onto the international art scene. Money was flowing into the art world like never before. Art prices were rising fast on the auction scene. In 1981, Julian Schnabel had a joint show at the Mary Boone and Leo Castelli galleries, the most glamorous galleries at that time. With his oversize ego and bombastic statements, Schnabel’s vision of the role of the artist was entirely the opposite of Hantaï’s. In just a few years art had abruptly turned from an activity of countercultural, critical thinking and subversive practice into one embracing conservative and capitalist values. Networking, producing, showing and selling overshadowed all other aspects. For artists in their mid-careers, as Hantaï was at the time, who were shaped by the existential questions that emerged in the aftermath of the Second World War, the new order felt too much like an unacceptable Faustian deal.

Pollock and Matisse are most often invoked when trying to grasp Hantaï’s pliage work formally. We will reach out to both of them to examine the act of self-inflicted violence of a painter who decides to suspend the single activity that defines both his identity and his relationship to the world.

It might be worthwhile to examine more closely Matisse’s advice to his students placed as epigraph to our text, and to delve into the inherent violence of its image, especially in view of his own late paper cut-outs, where a pair of scissors, cutting through painted sheets of paper, creates shapes that speak to the viewer on their own, as if color were in fact the artist tongue. This powerful image, with its latent invocation of a paper cut on one’s tongue, is even more salient in French, where tongue and language are one and the same word:langue.

Matisse’s advice is all the more surprising because it is coming from someone who, at the same time, advocated an approach to painting akin to the comfort of a good armchair. Matisse is not an expressionist, even if in his Fauve days he flirted with its esthetic for a while, and thus the inherent violence of the painter’s relationship to his work is not externalized or visually expressed. Instead it is internalized, absorbed and transcended.

Speaking about his late silkscreen works exhibited at the Centre Pompidou in 1997, Hantaï will use words strangely echoing Matisse’s famous saying: “ça coupe très fort,” which could be best translated as “it slices through quite sharply.” This reference is also reflected in Hantaï’s own image of self-mutilation when, in 1999, on the occasion of a retrospective in Munster, Germany, he described his approach to pliage to Alfred Pacquement as akin to working blind with arms cut off.

Pollock’s slow descent into self-destruction in the last years of his life is a test case of an artist internalizing the unbearable tensions and contradictions at play in his work. What should we make of the fact that he did not paint at all in the last two years of his life? Was it an alcoholic burnout, as has too often been conveniently invoked? Was Pollock’s painter’s block his way to step back and reject the pressure and expectations of the art scene? Was it his way of refusing to participate in a game where he had become just a pawn, his way of letting painting slowly make its way back into his life without becoming the “phony” that, when drunk, he accused so many other painters to be?

We are not very far here from the roots of Hantaï’s own decision. Both are signs that something is amiss in the private contract between a painter and his painting, and in both cases it comes down to exterior social pressures. Pollock was less lucky than Willem de Kooning in the sense that his alcoholism took over his whole life including his painter’s mind, where for de Kooning it did not.

During his long career, Hantaï had stopped working periodically for extended stretches of time. One of these episodes took place in 1976 after the completion of Les silences rétiniens (the retinian silences), Jean-Michel Meurice’s film on the artist and lasted three and a half years. It seems that well before the 1983 decision, a pattern of pause for reassessment, of temporary withdrawal from engagement with the public, was already in place. In fact we could, without too much of a stretch, even posit that the rhythm of the pauses in his painter’s evolution somehow echoed the “unpainted” whites areas found in his pliages, which are called in French, very appropriately in this case, réserves. The first and foremost example of réserves that comes to mind in modern painting is Cézanne, who often left unpainted areas in finished paintings, especially in his Montagne St. Victoire watercolors, resulting in unending questions by his contemporaries as to whether these works were actually finished.

Thus, on one side Hantaï’s studio activity was structured by unpainted blanks on the canvas, and on the other by the reflective blanks or silences in the painter’s own activity, a rhythm where breathing space and breathing time were as critical to a painting’s success as to the well being of a studio practice. The French word réserves also carries a second meaning of having second thoughts or doubts about something. As, for example, in the case of a contract which could be signed “sous réserves de” (under the following conditions). It would seem that Hantaï’s work points towards a practice of the réserve both directly on the canvas and in his conceptual approach to his work.

In 1988, on the occasion of the publication of his book The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, Gilles Deleuze wrote a quick note to Hantaï, whose work he admired: “Your present withdrawal towards the private, your exodus, does not make you more absent but makes your presence more intense”. In the original French version of that note, Deleuze quite pointedly uses the word repliement for withdrawal. In English both pli and repli are translated as “fold”. In French repli also has a second meaning, which is that of a withdrawal, as in repli stratégique when speaking of an army’s strategic withdrawal from the front line. Would it be too far-fetched to see in Hantaï’s folding technique of pliage, a harbinger of his own withdrawal from painting as well? When speaking of his work in French or English, whether about the blank/réserves or of the fold/withdrawal, Hantaï’s ultimate act of resistance appears to have been ingrained in the very process of his pliage right from the beginning.

In another insightful essay in the same catalog, Agnes Berecz alludes to Hantaï’s strong, if not quite obvious, connection to Duchamp and to his famous statement bête comme un peintre (dumb as a painter). She proposes that Hantaï’s pliage method was a way of agreeing with Duchamp’s statement, by turning the creation of a painting into a blind activity that would make sense only after the painter had completely surrendered his creative will to its process. In the same catalog, writing on the Etudes et blancs series, Dominique Fourcade reminds us of Hantaï’s ambition to achieve a painting “without qualities”, a clear reference to Austrian writer Robert Musil’s own “man without quality” from 1930.

All three writers hint at different facets of a practice where the painter’s ego is progressively pushed out of his work. Hantaï’s ego had thus already left the building, so to speak, in his process of pliages well before his own physical withdrawal from the art market.

In her book Penser la peinture (Thinking Painting Through), the most recent in-depth study of Hantaï’s work to date, tellingly only published in French so far, American scholar Molly Warnock, for her part, examining the series of work directly preceding the pliages, insists on Hantaï’s search for “une peinture ordinaire” (an unremarkable painting). This series includes two of the most ambitious works of Hantaï’s whole career: “Ecriture rose” and “A galla placidia”, hung together in the Pompidou Center show for the first time since they were painted in 1958-59 over the course of a full year.

Although these two paintings don’t seem to announce the pliages formally, they are found in their complex combination of the religious, the erotic, and the sublime.(Georges Bataille’s shadow and his concept of excess hover over Hantaï’s studio right until the end.) It is there that Hantaï’s esthetic program of self-effacement gets started. It is also with the end of that series of paintings and the clean formal break made by the “Mariales” paintings — the first pliage works — that Hantaï symbolically rehearses his 1983 break-up with the art world.

In 1982, just before making his life-altering decision, Hantaï started work on a new series, the “Tabula lilas,” which was exhibited at the Jean Fournier Gallery in Paris in June-July of the same year. This series departed from the previous ones in one very significant aspect: Instead of being pre-primed, the canvas was left raw, almost unprepared, and the paint that he used to cover the folds was white, a color previously dedicated to the primed background of the pliages.

The “Tabula lilas” series was the last work that Hantaï would exhibit before “retiring” and the fate of these paintings strangely mirrors his decision. They irradiated a peculiar mystical light (which Dominique Fourcade associated with the lilac light emanating from Matisse’s stained glass windows in his Vence chapel), but because of the raw materials used, they quickly faded and “burned” in the daylight’s ultraviolet rays to such an extent that only one painting of the whole series has survived: A disappearance was already encoded into their own material and process.

To better understand the particulars of Hantaï’s decision one needs to compare it to other painters who withdrew from painting or exhibiting, a gesture that is more common than one would think. One example is that of Eugen Schönebeck (born in 1936), a slightly younger German painter, rediscovered in the fall of 2012 on the occasion of a show at the David Nolan gallery in New York. Schönebeck stopped painting in 1967 at age 31 and withdrew permanently from the art world. Even though Hantaï and Schönebeck’s styles and the personal motivations for their decisions are quite different, one cannot help but draw a parallel between them. In Schönebeck’s case, it was the impossibility (or the unwillingness) to resolve a fundamental contradiction at the core of his work, a refusal to compromise the values of a socialist ideal (even if understood as flawed) with the requirements of the capitalist market (whose flaws were only too obvious). It was a refusal to take sides, an insistence on the tension in the conflict, a way to put a finger on the wound, to make the viewer aware of the pain: a pain not exactly traceable to any specifics in the artworks, but that lies at the heart of a painter’s daily practice.

Hantaï’s own rejection of the “system” is not too far from Schonebeck’s. By refusing to exhibit, the painter cuts his tongue off again, but this time to prevent painting from speaking, to make public an act of private dissent. The contradictions he faced at this stage of his career were clearly unsolvable. For Hantaï, the path laid in front of him of further official and market-driven recognition at the cost of further compromises, went against the essence of his practice. In his eyes recognition at such a cost was not worth it.

There is also the example of Michel Parmentier (1938-2000) of the French painters group BMPT (which derived its name from the initials of the members’ last names: Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, and Niele Toroni). The members of BMPT, being of a younger generation, were directly affected by Hantaï’s work, not in their public strategies, but in their understanding of the contradictions at stake in the practice of painting. Parmentier stopped painting in 1968, seeing it as a medium too ideologically compromised to carry on with it. But he resumed his practice (with Hantaï’s help) in 1983, at the same moment when Hantaï himself had resolved to close shop. Parmentier’s work is a good example of the radical approach to painting in vogue from the mid-sixties through the seventies in Paris. We may wonder if perhaps the younger Parmentier’s example contributed to reinforce the older Hantaï’s decision?

In 1994, while putting together a proposal for a group show pairing European and New York abstract painters in collaboration with another painter friend for the Philippe Briet Gallery, I met with Steven Parrino (1958-2005) and Olivier Mosset (another ex-member of the BMPT group), and we discussed a list of possible participating artists. Our intention was to show Steven’s wrinkled “misshaped” paintings next to a “pliage”. I had until then assumed that Hantaï’s work would be as familiar to American painters of my generation as it was to me. To my surprise Steven had never heard of Hantaï’s work, but seemed excited by the description I made of it, and at the prospect of a visual dialog with it in the context of a group show. The show never materialized because the gallery where it was planned closed two months later, and the connection with Hantaï was never pursued, partly due to Steven’s untimely death. But the anecdote is a good measure of Hantaï’s lack of recognition by American painters of the generation who would have most benefited from exposure to his work. Earlier this year, this Hantaï/Parrino connection was finally clearly established in a group show at the Paris branch of the Gagosian Gallery, where both their works were presented along with those of the BMPT group members.

Hantaï’s silent withdrawal from and disapproval of an art scene ruled by market values exemplifies the conflict between a generation of painters coming to prominence in the 70’s for whom art was about the disappearance of the artist’s ego, while in the early 80’s, with the triumph of the society of the spectacle, the ego became the benchmark of all artistic measures. Only with time did Hantaï’s self-effacing gesture come to take such a heroic dimension, of a kind not seen since the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. This is where Hantaï meets Pollock again, not just because of his unique understanding of Pollock’s all-over, but because Hantaï’s stubborn refusal to compromise echoes Pollock’s own self-destructive respect of his own work and his refusal to bow to social pressures about the unacceptability of a return to the figure.

In Hantaï’s gesture, the heroic and the sublime are internalized in the painter’s dedication to the integrity of his work, rather than in an externalized and spectacularized gesture, as the Neo-Expressionists of the eighties understood it, even through the filter of an easily shared “post-modern” irony. Hantaï’s silent withdrawal from the scene was first and foremost an act of quiet resistance, a refusal to play along in a rigged game and to reap its illusory benefits. A perfect and rare example of how ethics can sometimes trounce esthetics.

“I did not abandon Painting. What I left was its enrollment to the cause of the economy, and above all its function as a stand-in (bouche trou)”.

—Simon Hantaï

[Back to press]

Simon Hantaï and the International Scene

Hantaï in America

This text explores the origins of Hantaï's work in Abstract Expressionism, specifically Jackson Pollock, and further situates it in the context of developments in American 1960's and 70's art, with particular reference to Andy Warhol, Donald Judd, Bruce Nauman and Robert Smithson. This text was commissioned by Paul Rodgers / 9W and published in 2006. During the artist's retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, Paris (May 22 - September 2, 2013), this Carter Ratcliff essay was published, with its French translation, in the supplement for the June 2013 issue of Artpress.

In Europe, Simon Hantaï has long been recognized as a major painter. In the United States, he is nearly unknown. This is odd because he is one of the very few artists, European or American, who responded to Jackson Pollock’s poured paintings in a genuinely original manner. Pollock invented a new way to paint and Hantaï did the same. This was a remarkable achievement, considering that strong responses to Pollock nearly always began with the abandonment of paint and canvas. Exasperated by these materials, the future Minimalists—Donald Judd for example—gave Pollock’s dripping a literalist reading and then followed the logic of their literalism into real space, which they occupied with three-dimensional objects. Hantaï’s works are, first and last, paintings—works of pictorial art. Yet he dispensed with the traditional process of picture-making as thoroughly as did Pollock, who exchanged his brush for a stick from which to drip and pour his pigments. Keeping his brush, Hantaï redefined his art by redefining the canvas.

Basic to the idea of painting is the flat, blank, or neutral surface of the canvas. For centuries, this neutrality was unquestionable. Hantaï not only questioned it, he banished it with a new way of making a painting called pliage, from plier, to fold. Before he begins to paint, Hantaï folds his canvas in a complex pattern that hides some of its surface and leaves the rest available to his brush. Having applied paint to the exposed areas, he opens up the canvas, and sees, for the first time, exactly what he has done. Hantaї’s “folding method” is clearly very different from Pollock’s “drip method”, resembling it only in its originality and in the power of its response to questions raised by Pollock. With his unencumbered gesture, Pollock had redefined figure and ground. He redrew the boundaries of pictorial space. Hantaї’s folding method completely rethinks the ground, and perhaps the very idea of painting itself, for his imagery—with its play of light and dark, of positive and negative—is in part the upshot of decisions made before any paint is applied. Folding relocates the painter’s intention. In the process, vision finds a new relationship to the other senses.

There is more to say about Hantaï and Pollock, about Hantaï and the history of art in the past half century. That so much needs to be said is surprising. Only rarely does an American writer have the opportunity to survey the achievement of a major European artist for almost the first time in English. [1] Perhaps there was a moment, in the late 1970s or early ’80s, when Joseph Beuys needed a comparably detailed introduction to American audiences. It is difficult to think of another example. In any case, we need to set aside the presuppositions that, for decades, have hidden Hantaï from American eyes or permitted him to be seen in the United States, if at all, as a distant and nearly invisible monument.

No one is more acutely aware of this need than the artist himself. In 1998, Hantaï refused to allow his work to be included in an exhibition of French painting organized by the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The context, he felt, was unsuitable. At first glance, this objection is hard to understand. Born in Hungary in 1922, Hantaï has lived in France since 1949. Not long after his arrival, he was recruited to the Surrealist movement by Andre Breton. By the mid-1950s, he had broken with Surrealism, and in 1960 he invented the folding method. Since then, he has been recognized as one of the leading figures to have emerged on the stage of French art in the half-century after the Second World War. Why, then, would he refuse to be included in an exhibition intended to celebrate painters from his time and place? His refusal was all the more puzzling because one sees echoes of Matisse’s forms in certain of his paintings. In others, there are recollections of Cézanne’s light. Forced to categorize him, one would have to call him a French painter. His contribution to the art of his adopted country permits no other label. Still, for all its accuracy, it obscures a full view of Hantaï’s achievement. That, I suspect, is why Hantaï declined to be included in an exhibition of French painting.

What follows could be seen as a proposal for an exhibition that would place Hantaï in another context, quite different from the ones in which he has nearly always found himself. In this virtual setting, some of Hantaï’s neighbors would be Italian, for there is a rapport between his art and the arte povera that emerged in Genoa, Milan and elsewhere during the late 1960s. Some would be from other regions of Europe. However, most of the artists in this imaginary exhibition would be American. I have referred to Pollock, as Hantaï himself does. Tracing the development of the folding method and mapping its affinities, I will return to the Minimalists, who used industrial fabrication to replicate the readymade forms of Euclidean geometry. There will be occasion to mention the process and performance art that developed from Minimalism; the detached impersonality of Andy Warhol’s silkscreen technique, and earthworks, especially those of Robert Smithson, who pushed to extremes the idea that art is material—that is to say, not spiritual, conceptual, expressive, or in any other way immaterial. I don’t say that Hantaï makes common cause with Smithson or any other American artist. Yet the full significance of Hantaï’s achievement cannot be seen until his engagement with the most innovative American art of the 1960’s and ‘70’s is taken into account.

• • •

Entering the Art Academy of Budapest in 1942, Hantaï studied there, on and off, until 1948. Settling in Paris the following year, he experimented with frottage (rubbing), grattage (scratching), and other techniques discovered through Surrealist experiments, especially those conducted by Max Ernst. Always, he painted, arriving quickly in Paris at a biomorphic style that hovered in the ambiguous zone between figurative and non-figurative imagery. His first solo exhibition, in 1953, was introduced with much fanfare by Breton. Only a few seasons later, Hantaï renounced Surrealism. From the point of view of Breton and the Surrealist faithful, he had betrayed the promise of revolution through art. Of course, the Surrealist revolution, which was to have put ordinary reality on a new and improved footing, never occurred. From the perspective provided by Hantaï’s later work, one might say that Surrealism turned out, despite its promises, to be fatally conservative—not so much a revolutionary movement as a cluster of academic styles devised to illustrate a yearning for the new. Leaving Surrealism behind, Hantaï achieved something entirely new. But not immediately.

Between his Surrealist period and his first folded canvases came a gestural interlude and a brief association with the French tachiste painter Georges Mathieu. Like Mathieu, Hantaï was driven by the example of Jackson Pollock to develop a repertory of slashing, curving, zigzagging brushstrokes. Hantaï’s improvisations are often more deliberately tangled—more desperate—than Mattheiu’s. He seems to have understood from the start that there was no real point in coming up with variations on Pollock’s gesture. Gesture was somehow the point, and yet, as Hantaï understood, it could not be gesture of a painterly kind. It could not be expressive nor could it be representational, not even in the most attenuated manner. No gesture of the hand, no dance in the presence of the canvas, would do. In 1960, Hantaï arrived at the solution that has sustained his art since then. He would displace gesture to the canvas itself.

• • •

As it happened, Hantaï did not reinvent painting until he had brought his gestural interlude to a grand culmination. In 1958, he set out to cover a very large canvas with texts gathered from a variety of sources: Biblical, theological, metaphysical, poetic, psychoanalytic. After a year of copying these passages in a minute hand, Hantaï’s inscriptions acquired a thoroughly pictorial texture. His texts were now illegible, and yet he had filled the canvas—now called the Écriture Rose—with an aura of significance, a dense cloud of implication. The work later entered the permanent collection of the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, where it occupies a crucial place in the museum’s account of twentieth-century art.

We can be certain only that the Écriture rose has to do with language. Scanning its surface, one thinks of a medieval scribe devoted to an endless task. Nonetheless, Hantaï’s inscriptions did come to an end. We might see the Écriture rose as the grand residue of a long, almost ceremonial meditation on the part that language has played in the development of Western painting. The theorization of the pictorial was launched in ancient Greece. Since then, painting has been caught up in a conceptual apparatus of extreme intricacy. Perhaps Hantaï felt that, by writing his way to the end of language, so to speak, he could extricate painting from theory’s mechanisms. At any rate, when the Écriture rose was finished, he said, “Avaler les mots.” [2] “Dispense with words.”

Having set language aside, Hantaï placed his canvas on the floor and subjected it to a series of actions: “folding, knotting, trampling underfoot,” to quote from a list made by Anne Baldassari, curator at the Musée Picasso. [3] This behavior is implied by the word pliage, already noted, and yet Baldassari’s account of Hantaï’s procedure is helpful because she stresses its repetitiousness. The labor required by pliage is onerous and silent, or nearly so. Remarking on the “rustling” of the canvas as it submits to folding and trampling, Baldassari leaves it to us to imagine the matter-of-fact violence Hantaï inflicts on the canvas as he flattens it in preparation for the application of paint to those portions that his folding leaves in view. [4]

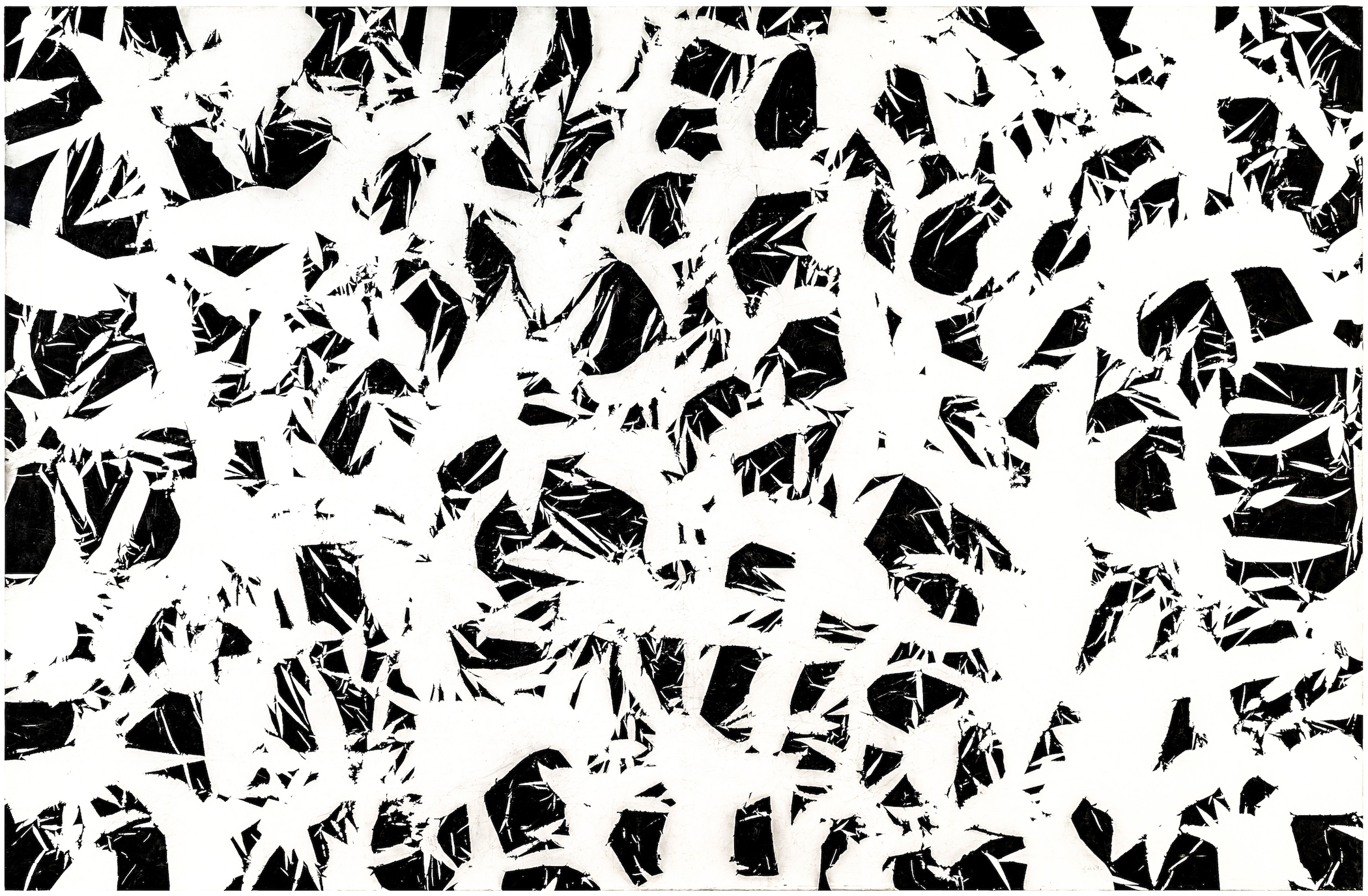

The first of the folded canvases are called Manteaux de la Vierge. This becomes, in English, Mantles or Cloaks of the Virgin, a title often shortened to Cloaks. They are dense, impacted, encrusted. Some have the look of earth soaked by a heavy rain and then dried and cracked by harsh sunlight. There is a suggestion of “craquelure,” as conservators call it, those networks of fine lines that often appear in the surfaces of old oil paintings. In Hantaï’s canvases from 1960 on, the “craquelure” can be severe and, far from obscuring the image, helps to constitute it.

Hantaï’s departure from the Surrealist ranks brought his career as a figurative painter to an end, and yet it is easy enough to read subject matter into his later work. After the cracked mud of the more heavily encrusted Cloaks come leaf- and petal-shapes of a new series begun in 1967 and entitled Meun, after the village in the forest of Fontainebleau to which the artist and his family had moved two years earlier. Like Rorschach blots, Hantaï’s paintings invite no end of speculative interpretation. But what, precisely, do they represent? The method that produced them, no doubt. The folding method is a kind of self-portraiture, a way for a painter’s method to make images of itself. Yet these “portraits” are incorrigibly ambiguous, filled as they are with the chance effects that the folding method not only permits but invites. What are we to make of details of form and texture that cannot be seen as fully intended? Where, come to think of it, are we to look for Hantaï’s intentions? Marcel Duchamp, the modernist godfather of chance in art, lurks somewhere in the genealogy that Hantaï, like all ambitious artists of the period, invented for himself. Chance is a factor, as well, in Pollock’s drip-method, which, as we’ve seen, was essential for Hantaï as he looked for a way beyond Surrealism.

• • •

The distance from the Cloaks to the Meuns, 1967-68, is vast, too vast to be traversed in one step. By 1962, texture had given way to rough forms, distinct but not separated from one another. The underlying ground was unable to emerge. Then, in the mid-1960s, the canvas ground began to assert itself more forcefully. By 1967, figure and ground had claimed nearly equal portions of the painting’s surface. The Meun series was under way. Over the years, Hantaï has now and then repeated a certain phrase: “Toujours et encore les ciseaux et le bâton trempé.” [5] “Always and again the scissors and the dripping stick.” The latter refers to Pollock’s drip-method; the “scissors” belong to Henri Matisse, who made some of his late works by cutting and pasting sheets of colored paper. With the flat, quasi-organic shapes of the Meun series, Hantaï evokes Matissean decoupage or cutouts—and he reminds us that Pollock was not the only modernist painter to subject his method and thus his medium to drastic revision. For the cutouts introduced a new compositional element and yet made no break with painting. With his cutouts, Matisse used decoupage to extend painting into new territory. For a century or more, expansions like these have kept painting alive and flourishing.

To cut shapes from colored paper is to perform an act no less physical than directly applying paint with a brush. Yet painting longs to transcend the physical—not that the tangibility of paint on canvas was ever denied. Nonetheless, figurative painting can be understood as an attempt to persuade the viewer to look through a painted surface into the depths of imaginary space. With the development of abstract painting, this yearning to escape physicality intensified. Avant-garde painters and their critics talked of pure color, pure gesture, and “pure opticality.” This rhetoric of purity reflects a bias against materiality, against the body and sensory experience—with the exception of the visual, for vision can be assimilated to the immaterial realm of thought. Thus we say, “I see” to signify understanding.

This bias in favor of vision appeared early on. According to the pre-Socratic Heraclitus, “The eyes make better witnesses than the ears.” In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates spins a story of the soul as a charioteer, guiding a pair of horses upward, beyond earthly things, to a glimpse of the eternal Forms of ultimate Reality. Michelangelo invokes the Platonic glimpse when he says, in one of his sonnets, that the true sculptor is the one who can see the essence of a form in a brute block of marble. Relinquishing the visionary privileges to which he and every other Western artist is heir, Hantaï talks of “painting without seeing . . . looking elsewhere.” [6] “With pliage,” he says, “I put out my eyes . . . blind calculation . . . a bet on one’s blindness.” Then: “Do away with the screen.” With these fragmentary utterances, Hantaï points obliquely, tactfully, to his accomplishment, which was to place his medium on a new basis. After inventing the folding method, he dispensed with the transcendent—one could almost say, magical—idea of vision that we inherit from Plato and his many successors, who include a surprising number of contemporary art theorists and historians.

The key image in Hantaï’s commentary is the screen—not the cinematic screen, not the screen of the television set or the computer, but a screen prior to any of these: the canvas, the surface where the painter’s image is traditionally projected and, in the process, comes to be seen as impalpable, immaterial, ideal. Hantaï talks of doing away with “the screen” to suggest that his paintings are not sites where the ideal is revealed. So his canvases need not present themselves as immaterial or, rather, as lengths of fabric only incidentally material. The folding method insists on something obvious but traditionally overlooked: the canvas is dense and frankly palpable, and this frankness is what distinguishes the paintings of the Meun series from the late cutouts of Matisse, to which they bear an inescapable resemblance.

Hantaï does not, however, intend the Meuns as “critiques” of Matisse’s cutouts. He did not put out his eyes, figuratively speaking, to protest the vision of Matisse or Michelangelo or Plato. He has never, so far as I know, expressed doubts about the truths delivered by the visionary tradition those figures exemplify. Nonetheless, his invention of the folding method suggests that, as the 1950s ended, he no longer saw painting as a matter of transcendent truth. He no longer saw painting itself—not, at least, as it had been seen for centuries. With the folding method he began to feel his paintings as much as see them. As a work progressed, vision became the partner of touch, not its superior, and one imagines that it was sometimes a decidedly junior partner.

Or all such distinctions were lost in the interplay of the artist’s tactile, conceptual, and, of course, visual intuitions. By demoting vision, Hantaï merged the senses and undermined the ancient, persistent habit of seeing body and mind as separate and distinct. It is tempting to say that, with the folding method, he found a way to make paintings in a bodily mode. Yet one could just as well call the folding method a conceptual mode, in light of the parts played by the initial idea of a painting, by subsequent revisions, made as the work progresses, and by calculations about chance, which guide the artist from start to finish. At once bodily and conceptual, a physical method and a theory enacted, the folding method requires a unified self, a self in full.

• • •

"What interests me is what approaches the indeterminate, as in Pollock, who abandons easel painting, the frame, and with them all security" Simon Hantaï, 1998 [7]

Pollock took exemplary risks, and Hantaï was not the only artist to respond. During the late 1950s in New York, Pollock’s full-body gesture prompted Alan Kaprow, for example, to invent the Happening. Cued by a sketchy scenario, members of the audience would perform a sequence of quasi-improvisational actions. The work was fugitive, vanishing as it appeared. In Paris, Yves Klein found yet another way to insist on the presence of the body. Slathering nude women with paint, he instructed them to press themselves against lengths of canvas unfurled on the floor. With the imprint of their flesh, they generated the image. These works of Anthropometrie, as Klein called them, can be seen as absurdist pranks—jokes prompted by the changes painting was undergoing in the decades after the Second World War. Nonetheless, they are elegant. And their lush traces of flesh are similar to the forms in Hantaï’s Meun series. At the very least, Klein’s response to Pollock alerts us to the figurative aura of the Meun canvases. And it shows us how insistently painting’s relation to the body was shifting. Much else was changing during that time—so much that, to provide Hantaï’s innovations with their context, we must pull back for a wide view of the sprawling, turbulent period known as “the Sixties.” This was a time of agitations, which began to simmer late in the 1950s and boiled over with a vehemence that persisted into the ’70s.

The ’60s were a time of confrontations, many of them instigated by the young, who gave youth itself an adversarial aura. Among the novelties of the period were the clothes, long hair, and body paint of the hippy movement, all of which may well look silly in retrospect. Nonetheless, the hippy look served as a costume for new attitudes toward far from trivial matters—sexuality and the use of mind-altering drugs, for obvious examples. Students are always impatient with the routines and compromised ideals of the academy. During the ’60s, that impatience exploded, along with a determination to change the rules of political play. Throughout the Western world, substantial numbers of young people were suddenly demanding that their nominally democratic governments live up to their professed values. Driven by no very clear ideology, these developments were local and, of course, varied. As Hantaї was painting the Meun series, unrest in France culminated in the events of “1968”. In the United States, the restlessness of “youth culture” was more diffuse, though it did find a degree of focus in protests against the war in Viet Nam. At first glance, it is difficult to see what any of this has to do with developments in the art of the ’60s, and yet I think there are significant links.

To return for a moment to a matter of fashion—the long hair and sexually ambiguous clothes of “youth culture” were not intended merely to offend stodgy sensibilities. In the offense was a challenge to the old, patriarchal model of society. The use of illegal drugs challenged the law, as did war protest at its most violent. During the ’60s hardly any established power went unchallenged, certainly not that of the universities or of politics as usual. Corporate policy was questioned, along with the economic and military role of the West in the developing world. Playful or earnest, these protests were by and large the work of young people with unseasoned sensibilities. On the plane of art, comparable challenges were made. A sharp difference in tone separates the young from the mature, and that may be why it is difficult to detect any connection between, say, student uprisings and the innovations that define the major art of the ’60s. The connection is there, nonetheless, and it emerges—it becomes unmistakable—the moment we notice how thoroughly those years were shaped by a shared purpose. On the plane of art, as in the street, the ’60s protested authority—particular authorities, the very idea of authority, and the absolute truths to which authority appeals for legitimacy. By extension, elitism in all its manifestations, including the cultural, was questioned. “Youth culture’s” rejection of patriarchy and militarism is obvious. Not so obvious is the rejection that opened the way to the work of Hantaï and the Minimalists and others, who shared a desire to challenge what passed as the laws of art, in Hantaї’s case with the invention of the folding method, and in the case of the Minimalists with outright abandonment of painting for a medium that, as Judd correctly noted, did not qualify as sculpture in any traditional sense.

In 1967 Bruce Nauman commissioned a fabricator to write the following words in spiraling neon: “The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.” Against the backdrop of this artist’s other works, this motto acquires an ironic edge. Toward the end of the ‘60s, irony of this sort was still new. For nearly two and a half millennia, the highest purpose of art had been to reveal “Mystic Truths” about absolute, other-worldly realities. Moreover, faith in art as a medium of the absolute persisted well into the twentieth century. Though the avant-garde was nominally secular, its leaders—Wassily Kandinsky, for instance, or Piet Mondrian—were no less spiritually inclined than medieval artists. So it is no surprise that, early on, Pollock’s admirers glimpsed in his webs of dripped and spattered pigment transcendent truths about the modern self, the American experience, the essence of painting, and more. Then came the ’60s and, with them, headstrong doubts about authority and a tendency to reject privilege and elitism in any form.

Theological or metaphysical or aesthetic, transcendent truths have an authority that is—for the faithful—beyond question. In the absence of doubt, one feels secure. Hantaї’s attitude in this regard is nuanced. He did not reject that sort of authority as much as decide at a certain point to carry on without it. Pollock had abandoned “all security” and so would he. Going it alone, he would make his way into a future in which everything was up for grabs.

In order to under-stand an artist of Hantaï’s independence, we have to see him as isolated—not absolutely but, rather, to a degree that disconnects him from all but those artists whose originality is equal to his own. To grasp what Hantaï put at stake, it helps to see him in the company of those American artists of the ’60s who marked the period—Donald Judd, Andy Warhol, Robert Smithson, and a few others who, like Hantaï, turned to a future with no promise of ultimate truth, absolute purity, or redemption of any kind.

With industrial fabrication, Judd and the other Minimalists distanced themselves from their works and rejected the elitism of “high art”. Hantaï achieved a comparable effect with the folding method, which, as he has said, enables one “to expel oneself from the painting.” [8] The folding method makes certain decisions without consulting the artist. Yet there was a difference between him and his American counterparts among the Minimalists. They were theorists and polemicists. Hantaï is not, for all the brilliance of his remarks on painting. Just as he cultivated a certain “blindness,” mixing the clarities of vision with the intuitions of touch, so Hantaï has always undermined the false certainties of theory with immediate, ad hoc speculation.

Guided by their doctrines of “the specific object” and the “good gestalt,” Judd and his colleagues took carefully measured steps along clearly blazed paths. This theoretical bent persisted into Minimalism’s aftermath, producing a logic of stark reversals: rigidities of Minimalist geometry gave way to the “anti-form” of scatter-pieces and the wilder varieties of process art. Process led to performance, which displaced Minimalist literalism to the body, and to the real-time imagery of video art, with its aesthetic of temporal literalism. Video aside, all these distinct and successive developments have equivalents in the evolution of Hantaï’s folding method, and, astonishingly enough, all of them are present from the outset. For the folding method entails a kind of performance, even as it endows the folded and unfolded canvas with a materiality as dense and immediate as that of the Minimalist object. If there is performance, there is process. And the aleatory, Duchampian effects of the folding method inject an element of anti- or non-form—sheer hazard—into the deliberately shaped patterns of Hantaï’s imagery.

Like the Minimalists, Andy Warhol borrowed alloverness from Pollock and revamped it in a geometric manner, chiefly by imposing a grid on the pictorial field. In certain ways, Warhol was as much a Minimalist as Judd or Morris. And so he too was of interest to Hantaï, even though he filled his grid-patterns with the found images that qualified him as a Pop artist. Labels aside, Warhol’s photo-silk-screening is just as mechanical as the fabrication Morris and Judd delegated to factory workers and parallels Hantaï’s folding method . Exchanging traditional studio practice methods for commercial, hands-off methods of production, these Americans of the ’60s dispersed the other-worldly aura of the unique, hand-made object, again as did Hantaï’s folding method in part. The difference is that Hantaï, however, made his paintings by himself in the studio, using the painter’s familiar materials. His hands-on method preserves his connection with Matisse and the entire tradition of Western painting, even as he ceases to feel that tradition’s yearning for transcendent, immaterial purity. “L’impureté est la vraie situation,” Hantaï has said. [9] “Impurity is the true situation.” Or the “real situation”? However we interpret this comment, it seems fair to suppose that Hantaï has no interest in transcending the complexity, contingency, and ambiguity of the situations in which he finds himself. These are of his own devising, complicated at his own insistence, and so, while there are many affinities, there is no ‘one-on-one’ correspondence between his development and that of the American artists who share his interests and attitudes.

• • •

With his folding method, Hantaï invited results at least in part unforeseen. Warhol, too, let contingency insinuate itself, welcoming the streaks, blotches, and other glitches generated by his slapdash manner of silk-screening. Moreover, his images themselves feel unintended, as if he didn’t decide to paint Elvis or Marilyn so much as let himself be drawn into the decision by the yearnings and impulses animating ordinary society—or “consumer culture.” Though Warhol may not have given the accidental and the arbitrary an energetic embrace, he certainly accepted them, and this acceptance released him from the priestly task of unveiling transcendent truths. His truths are nothing if not down-to-earth, and his fictions of glamour are anything but other-worldly. An exemplar of the ’60s, Warhol must be credited for contributing to the demystification of art. Yet this achievement came at the price of cultivating an indifference to the distinction between art and popular illustration, which does exist for all that.

Warhol blocked the upward swoop of transcendence with vacuity. Having begun as a commercial artist, he had no qualms about filling the precincts of art with mere decoration or, in his commissioned portraits, sheer flattery. This insouciance puts him in sharp contrast to Hantaï, whose renunciation of transcendence has the weight of a resolve not to shirk the burden, literal or metaphorical, of painting’s traditional materials. That burden, at its most demanding, is historical, and that is why the full meaning of Hantaï’s art comes into view only against the backdrop of his medium’s long and complex past.

Again, this is the medium—paint on canvas—that Judd and other Minimalists rejected on the way to their version of the anti-transcendence that pervaded the ’60s. With that rejection, they severed their connection to the past. Or that is what they thought they did. In fact, Minimalism is haunted by everything that it rejected, all that it cannot acknowledge, unlike the art of Hantaï, which is in touch with its origins, whether ancient or recent, and gives us new, down-to-earth ways to understand them—to understand, in other words, earlier stages in the history of painting. Turning from the products of Hantaï’s folding method, for example, to religious paintings from earlier centuries, is to glimpse, however dimly, the worldly, entirely human impulses that mingle with—indeed, motivate—even the most fervently spiritual art.

To be haunted by the past one denies—this is a heavy price to pay for innovation and yet it is no heavier than the one Warhol paid, not all that reluctantly, by ignoring the border between art and popular illustration. Looking at Minimalism and its aftermath in the light of Hantaï’s paintings, one sees a great deal of American art clustering in yet another border region. Here life and art meet and negotiate their differences—or, it may be, pretend that there are none.

As process artists, performance artists, video artists, and others extended Minimalist literalism ever further into ordinary life, art was more and more often understood as a kind of “investigation.” Art devolved into the documentation that one so often sees in contemporary galleries and museums. In work of this sort, there is no question of the old-fashioned transcendence that used to supply art with its vocation, for there is no question of art.

At this bleak juncture, one thinks again of Bruce Nauman, not the ironist who mocks “Mystic Truths”, but the melancholy figure who has acknowledged, however glumly, that there are no such truths to be had. In 1967 he cast in greenish wax the portion of his body that stretches from his right hand to his mouth. Entitled, fittingly enough, From Hand to Mouth, this literalization turned a body fragment into a bizarre variation on a Minimalist object. To live from hand to mouth is, of course, to live precariously, on whatever meager morsels can be scrounged up in the unreliable present. By evoking this sort of deprivation, Nauman may well be offering an image of life after the failure of transcendence—a life impoverished by the loss of absolutes, the impossibility of “Mystic Truths.” For his colleague Robert Smithson, that impossibility was invigorating. It opened the way to the real in all its vividness.

Seen from the direction of Hantaï’s Europe—a culture no longer in thrall to traditional beliefs about the absolute—Smithson is a sympathetic figure. The two artists share similar attitudes to notions of material immanence and a certain tendency towards the profusion or excess that is to be found in the real world. With earthworks, films, essays, and more, Smithson advanced the idea that everything, even language, is material. Furthermore, he believed that matter will always resist our attempts to impose order. Far from lamenting the world’s inherent, irredeemable disorderliness, Smithson reveled in it. His earthworks are monuments to their own, gradual capitulation to the entropic forces lurking in the very structure of matter. All this is metaphorically present in the folding method and, together with a gleeful acceptance of contingency, gives Hantaï an affinity with Smithson. However, Smithson is the inventor of a New-World sublime, tinged with science fiction, linguistic theory, geological speculation, anti-utopian skepticism, and a quasi-erotic fascination with decay and death. Ultimately, the American’s indifference to painting—and to the entire history of art—puts the two at a considerable remove from one another. They are separated even further by disparities of scale.

Meaning, Smithson believed, is to be found by attending to particulars. Hantaï, one might speculate, would not disagree. However, the two artists had divergent ideas about the particulars worthy of attention. Smithson was obsessed by the intricacies of crystals, the geography of lost continents, quirks in the personalities of Mayan gods, and other matters that send the imagination spinning away in wildly speculative orbits. His art evokes a past that is archaic insofar as it is human and often attains the scale of geology or the interstellar infinite where human measure is annihilated. His futures tend to vanish into his fascination with entropy. So there is a last contrast to be drawn between this artist of the American “Sixties” and the European Hantaï, whose sensibility binds him to the densely woven patterns of individual experience.

For the materialist Smithson, the freedom to dispense with transcendence was to launch art on trajectories that leave the immediacies of the familiar far behind. That same freedom brought Hantaï’s art into ever-closer, ever more conscious contact with precisely those immediacies. For his art preserves and intensifies the human scale, the scale of the body’s actions. The folded paintings awaken us to the present we share with these objects and with one another. As for the future—that it might be livable is suggested by the humane drift of Hantaï’s meanings, most of which remain to be enunciated.

• • •

To return to my account of the folding method and its development in Hantaї’s painting, the Studies of 1969 break up form with a multiplicity of folds. The more folding, the more insistent the incursion of blankness into the zones of color. It is here that we can define the fundamental innovation of the folding method when compared with Pollock. For, whereas in Pollock’s all-over field the ground is on equal terms with his web of poured and dripped pigment, in Hantaї’s Studies of 1969 the ground becomes dynamic. It is active, not simply the passive recipient of painted form, and begins to dominate the composition. Jagged patches of white canvas become forms in themselves, and the image is a flickering alternation of light and dark. “It was while working on the Studies,” Hantaï has said, “that I realized what my true subject was: the resurgence of the ground underneath my painting” [10]. Form is ‘relativized’ and the ground resurges to claim its prerogative. This resurgence continued with the White Paintings of 1973-74. Blankness is now predominant. To hold their own, the painted areas of the canvas display a wider range of hues. In the Meuns and the Studies, form was monochrome. Now forms range across the spectrum, as if their diminishment had given them greater mobility in the realm of color. In some of the White Paintings, the play of hue is a subtle flickering with the power to recall the palette of Cézanne’s later paintings.

The transition from the White Paintings to the Tabulas, which are begun in1974, brings another abrupt change in the history of the folding method. All at once, scattered imagery became regular. Hantaï was now making grids: row upon row of small, squarish patches of color separated by crisscrossed streaks of white. The first of the Tabulas brought his imagery closer to that of Minimalism than it had ever been. Yet the artist points to a different and far more personal source for these grids of the mid-1970s: a photograph of his mother as a young woman. The apron she wears is gridded—that is, heavily creased in a squared-away pattern produced by the traditionally Hungarian manner of folding garments of this kind. By retrieving this photograph from the past, Hantaï makes an indispensable point: art is not solely a matter of formal problems and aesthetic issues. It concerns, as well, the artist’s sensibility as it is shaped and sustained by his memory. The grid, it seems, has a thoroughly personal meaning for Hantaï.

Tabulas continued to appear from 1974 until 1976. Then, after an interlude of six years, they reappeared, with the grid unit significantly enlarged. As the second phase of the Tabulas, begun in 1980, progresses the forms are once again invaded from the interior ground by flashes of white canvas. The effect of a grid prevails, despite the flowering of big, sprawling forms reminiscent of those in the Meun series and the White Paintings. Order and disorder in balance, Hantaï enlarged this resolution to an astounding degree in a subsequent series of Tabulas, which went on view at the Capc, Entrepôt Lainé, in Bordeaux soon after its completion. Though the museum’s galleries are vast and high-ceilinged, these paintings covered their walls with ease. Having raised alloverness to the scale of monumental architecture, Hantaï stopped painting. Carrying cessation a step further, in 1994, he destroyed most of the immense Tabulas he had shown at Bordeaux.

• • •

As Hantaï cut up the Tabulas of 1980-81, he saw that some of their bits and pieces stood up as paintings in their own right. A new series was emerging. Entitled Laissées—Left Overs—these canvases have a cousinly resemblance to certain Studies and a more distant connection with the Meuns. With their slashing passages of white canvas, they recall the White Paintings, as well. Finally, though, they are closest to the late Tabulas—in a fragmentary way, they are the late Tabulas—and they form, as well, a laconic summary of all that preceded them.

With his scissors, Matisse had turned colored paper into a material, into an equivalent of pigment applied with a brush—that is, pigment applied in the hope of producing an image that transcends its own physicality. Hantaï’s scissors insisted that canvas is palpable, a painting is an object, the pictorial is physical. But not solely physical. Nothing is purely one thing or another. The canvases in the Left Over series are fragments and wholes. They are accidents of a sort, the results of an afterthought, and yet they also serve as emblems of the artist’s ability to rethink his grandest works—the Tabulas he exhibited at Bordeaux. Presenting the clarity of final statements and the elusiveness of every other series in Hantaï’s oeuvre, the Left Overs are luminous and dark, reassuring and discomfiting. They are elegant and yet elegantly forlorn. They are like orphans whose self-sufficiency induces us to forget that they, too, have a past, even if it is impossible to trace in every detail. That past, of course, is the history of the folding method.

Looking back at the development of this method, one sees how tenuous it must have felt at every stage. With each variation in the process of folding and unfolding, Hantaï had to brace himself for a surprise. For he could not, of course, know how his latest experiment would turn out. And this surprise persists. Hantaï’s paintings continue to look new, which is, in itself, surprising—and not easy to explain. I think it must be a consequence of the contingency Hantaï built into his

process. His images are so rich with happenstance that they cannot be memorized and consigned to the past. Even the large forms of the Meuns, some of which are as recognizable as figures in a traditional painting, display quirks that make them difficult to pin down. Hantaï’s imagery is always of the present, and his present is not of the kind sought by earlier art—not a present generated by a transcendent vision. Not the moment of a Platonic revelation. This is an indispensable point, for it sets Hantaї apart from ‘modernist’ art, including Surrealism, which ultimately was no less devoted to other-worldly revelation than was the art of the Middle Ages or of ancient times.

Proponents of art as the revelation of ultimate realities, of transcendent truths, often talk of timelessness. ‘Platonic’ or ‘neo-platonic’ or ‘modernist’, they want art to loft them upward, toward a realm of eternal purity. To this yearning, Hantaï has replied more than once with a comment we have already heard: “Impurity is the true situation.” Indifferent to the ideals of pure form, pure color, pure gesture, his paintings mix the intended and the accidental, the intelligible and the enigmatic. Each of his works requires us to think our way into its past, to the method that produced it, and forward, into a future opened up by its power of metaphorical implication. Infused with the other dimensions of time, Hantaï’s present is impure, like the one in which we live, and so his paintings have the virtue of making us alive to our real, our true situations in all their contingency. Rather than mirror some timeless Truth, the products of the folding method create the truths that shape the world in their vicinity. And they encourage us to see that we do the same. We create our world as we make sense of it. For the most part we do this unconsciously, though it may well happen that, as we grapple with Hantaï’s art, we will find ourselves becoming increasingly aware of this power.

[1] . In recent years there have been two surveys of Hantaï’s work in American art journals. Tom McDonough, “Hantaï’s Challenge to Painting,” Art in America, March 1999, pp. 96-98, 128. Benjamin H. Buchloh, “Hantaï, Villeglé, and the Dialectics of Painting’s Dispersal,” October 91, Winter 200, pp. 25-35,

[2] . Simon Hantaï, quoted in Anne Baldassari, Simon Hantaï, Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1992 , p. 46

[3] . Ibid.

[4] . Ibid.

[5] . Hantaï, quoted in Simon Hantaï, exhibition catalog, Münster: Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschicte, 1999, p. 66

[6] . Hantaï, quoted in Simon Hantaï, Münster, p. 67

[7] . Hantaï, quoted in Philippe Dagen, “Les confidences d’un peintre en retrait du monde, Le Monde, March 15-16, 1998, p. 26

[8] . Hantaï, quoted in Simon Hantaï, Münster, p. 72

[9] . Hantaï, quoted in Didi-Huberman, L’Étoilement: Conversation avec Hantaï, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1998, p. 105

[10] . Hantaï in conversation with Paul Rodgers, Paris studio, 1994

[Back to press]

Letter from New York

by Ben Lerner, Lana Turner Journal, Jun 28, 2010

Dear Lana Turner,

There are two canvases hanging at Paul Rodgers' 9W gallery in New York that might cause you to rethink the last half-century or so of painting. Believe me, when I went to Chelsea to see them I didn’t intend to make any grand claims. But the work of Simon Hantaï, who died in 2008, can inspire such pronouncements. Hantaï, whose importance is widely accepted in France, is virtually unknown in the U.S., in part because, as a protest against the commercial focus of the art world, he refused to allow his paintings to be exhibited for twenty-five years, a refusal as inextricable from Hantaï’s work as Warhol’s embrace of the limelight was from his.